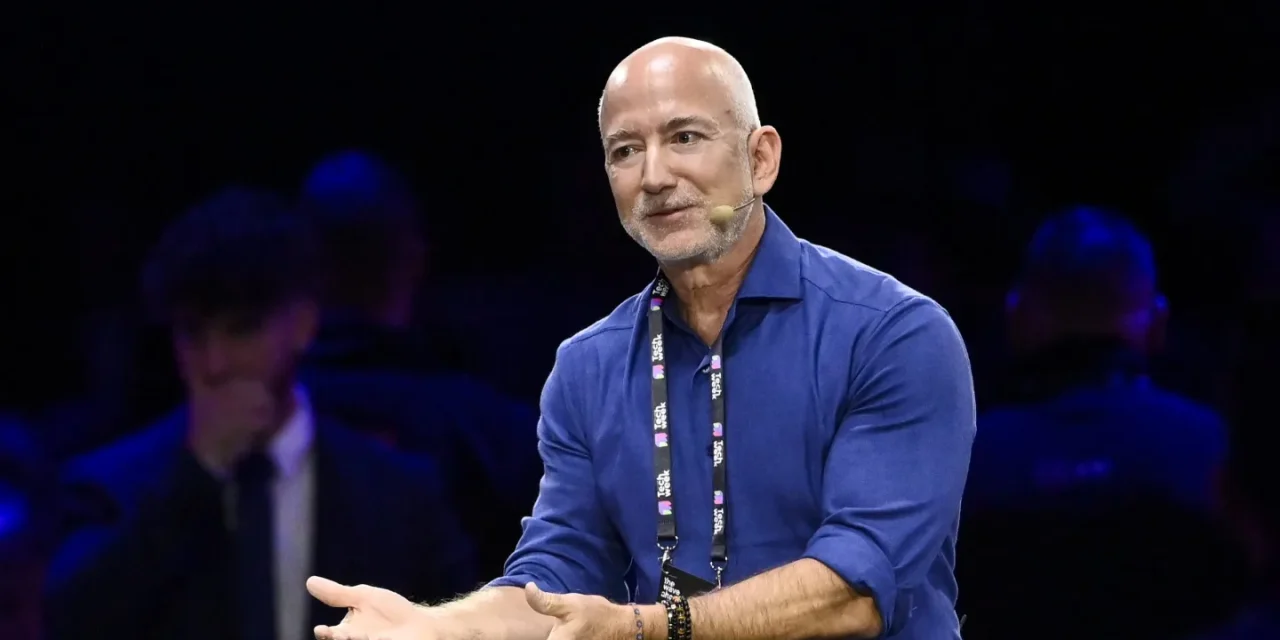

At Italian Tech Week, Jeff Bezos predicted that ‘gigawatt-scale’ data centres could be built in space within 10–20 years, powered by endless solar energy and free from Earth’s weather disruptions

The idea may sound futuristic, but it raises a pressing question: When data is stored or processed beyond Earth, which laws apply – and who enforces them?

As conversations about space-based cloud infrastructure move from science fiction to strategic planning, Incogni’s latest research suggests that governments are already falling behind in regulating data flows across borders right here on Earth.

A challenge that’s already real

Incogni’s study, Foreign Apps Harvesting Data, shows that data sovereignty is already eroding in the global digital economy.

- 6 of the 10 most popular foreign-owned apps used by Americans are Chinese-developed: including TikTok, Temu, Alibaba, Shein, CapCut, and AliExpress.

- Together, these apps have been downloaded approximately 1 billion times in the United States.

- On average, Chinese-owned apps collect 18 types of personal data per user and share 6 of those categories with external entities, often without transparency about where that data ultimately goes.

“Foreign data collection is already testing the limits of American privacy protection,” says Darius Belejevas, Head of Incogni. “Space-based data centres could make those limits even harder to police.”

The next frontier: data centres in orbit

Bezos envisions a future where space offers uninterrupted solar power, total uptime, and resilience from weather – potentially outcompeting Earth-based data centres on cost and reliability. But those advantages come with massive governance challenges.

Under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, the state that registers a space object retains jurisdiction and control over it. This prevents a total legal vacuum, but it doesn’t answer how personal or AI-generated data will be regulated once processed or stored in orbit.

Frameworks like the GDPR and CCPA may apply extraterritorially in principle, but practical enforcement becomes far more complex when data lives beyond any nation’s physical reach.

“The question should not be reduced to where the servers are,” Belejevas explains. “It should also dive into whether our existing laws can realistically follow data beyond national boundaries.”

From foreign servers to foreign skies

Even before space comes into play, Incogni’s research shows how difficult it already is to enforce privacy protections across jurisdictions.

Foreign-owned platforms, many headquartered in countries with different privacy standards, are collecting and sharing massive volumes of U.S. user data. Regulators often struggle to track where that information travels or how it’s used.

If those same systems move off-planet, the complexity multiplies. Accountability gaps widen, and cross-border cooperation could become nearly impossible when processing happens in orbit.

Why it matters now

The issue is far from being theoretical. The U.S. Department of Justice recently implemented restrictions on certain “bulk sensitive personal data” transactions involving countries of concern (Executive Order 14117; Final Rule effective April 8, 2025).

This reflects growing national-security attention on cross-border data transfers – and shows how terrestrial privacy challenges are evolving faster than regulation.

If Big Tech begins building infrastructure in orbit, existing laws may not be equipped to follow. Policymakers will need to anticipate this shift, ensuring that data protections extend wherever computing happens – including in space.

Looking ahead

Space may offer limitless energy and innovation potential, but without modernized data governance, it could also create limitless privacy risks.

“The real question isn’t whether we can build data centres in space,” says Darius Belejevas. “It’s whether our privacy laws can follow them there.”

For more information, visit https://incogni.com/about-us

To read more from Electrical Engineering, visit our NEWS page

Image Credit – Getty Images, Stefano Guidi